Exploring the IBM Graphical Filesystem

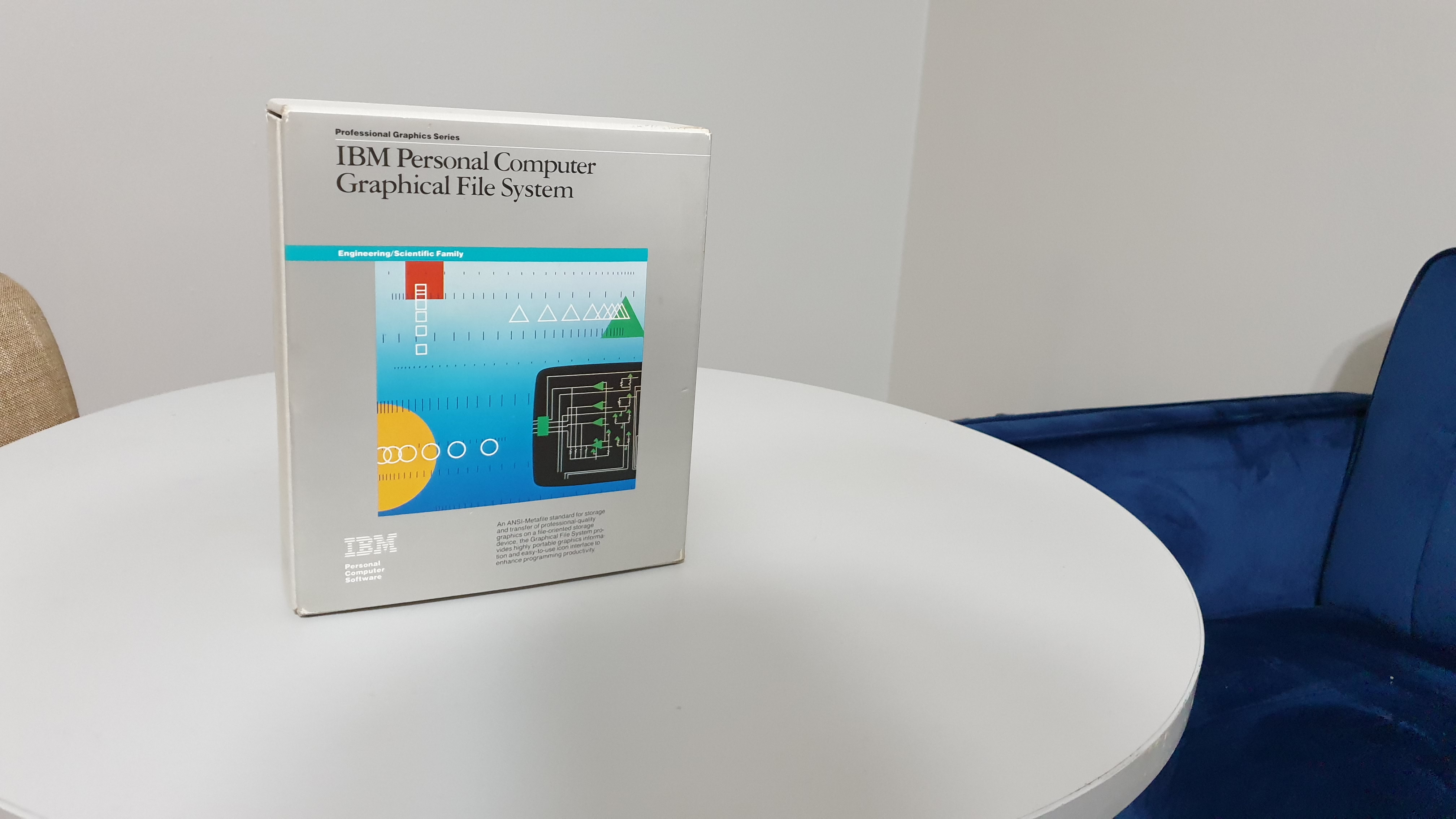

To be honest, I suffer from a bad case of 'curiosity killed the cat' at times. If I see something I don't understand, I find myself researching it to death until I do. It should come then as no surprise that this box of IBM strangeness ended up gnawing away on my soul for the better part of a month before I was finally ready to put it to bed.

Back of the Box

The name alone is already kinda interesting, and then I saw this closeup of the back which stated that it needs "one of the following compilers", and well, all I can say is: 'shut up and take my money'. Even after it arrived though, I was still no closer to solving this mystery. The blurb on the front just added more questions than answers.

“[It is] an ANSI-Metafile standard for storage and transfer of professional quality graphics on a file-oriented storage service. The Graphical File System provides highly portable graphics information, and easy-to-use icon interface to enhance programming productivity.”

I'm fairly sure you find one could find worse explanations, but it would take some effort. That being said, it shouldn't have taken as nearly long as it did to decode this block of mysteriousness had the included documentation had included something like a useful summary. I've really never seen that many pages of manual that technically describes something while failing to actually tell you anything useful ...

Even the pages where it describes the Graphical File System itself really don't help ...

Graphical File System Summary

The best I could get out of this is it had something to do with saving and loading graphics to file, but the documentation was remarkable short on details. In a broad sense, the manual could be broken up as follows: "A summary of IBM's Professional Graphics Series", "The Professional Graphics Series Drivers", and finally "Metafiles: everything you wanted to know, but were afraid to ask!".

We'll go into all these points in detail, but let's talk about what I actually found in the box. As usual, my findings come in YouTube form in addition to write-up, so do take a look, as does make a huge difference for me.

What Was In The Box ...

Beside the manual, there were five disks, three for the Graphical File System, and two labeled 'Professional Graphics Series Device Drivers'.

The five included 5.25 inch disks

All five disks were healthy, and my SuperCard Pro was able to read them without issue. The first three disks had what you might expect from a piece of development software: test applications, example code, and libraries for Lattice C, and IBM's FORTRAN and BASIC compilers.

The only thing that was really of note was METAFILE.EXE, which the manual calls the 'Interactive Interpreter', but it also became clear that there was more than meets the eye. The remaining two disks had the VDI subsystem, followed by a bunch of SYS files with one of the worst uses of 8.3 filenames that I've seen in awhile.

Professional Graphics Series Disk 2 Files

The manual also had a fairly long setup section. It appears that the Graphical File System is built around something called the Virtual Device Interface. It's here where I really began to fall down the rabbit hole.

Standardizing Graphics: The Graphical Kernel System

Professional Graphics Series Disk 2 Files

To be honest, what I found sorta surprised me. When most people think of early graphics, I tend to think in terms of Apple's QuickDraw, Microsoft's GDI, or even Adobe's PostScript. These were the big players, and aside from Apple migrating to PDF, all of them have continued to the present day. As far as graphics go, it has always seemed to be a world of 'pick your own proprietary standard'. So if you had asked me before if I thought that not only ANSI but ISO as a whole had actually tried to standardize graphics, I'd probably gone with "[citation needed]".

![[citation needed]]](https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/wikipedian_protester.png)

To be fair, the GFS manual does actually talk about the Graphical Kernel System, but in such a way that it makes it sound like a product, and not an actual specification. As I would find out much later, there is in fact a reason for this.

Graphical Kernel System in the GFS Manual

Unfortunately, the actual standards themselves appear to be paywalled, but I was able to gleam some bits through heavy Googling. The GKS system essentially worked as modern vector graphics do today. Instead of simply saving and loading a bitmap, drawing commands are stored in a series of commands, and then rendered at runtime. This is provided through Virtual Device Interface that I talked about earlier.

Actually, I was rather surprised that this existed not only in 1984, but actually dates back as far as the 70s. While vector graphics were an old concept even by the 1980s, I had always assumed that they had essentially remained proprietary affairs throughout this period. That also provides a good way of actually showing the impact of what something like the GKS and vectorized graphics could actually do.

TrueType Sizing Example

The absolute best example I can give of the importance of vector graphics, and the underlying principles at the heart of the Graphical Kernel System is fontfaces. Very early fonts were essentially bitmapped images; you couldn't freely resize them, you needed a given font in a given size to use it. This is obviously rather undesirable for multiple reasons. Adobe created Type 1 fonts, and Apple created TrueType in an attempt to defeat this by defining fonts as a series of drawing commands instead of static images. This leads to the ability to freely change and modify font sizes on the fly.

With the Graphical Kernel System (and vector systems in general), images could essentially be dynamically shaped and modified for their surroundings. Want to dynamically resize a chart? Go for it. Need to zoom in to add more detail? Not an issue! In short, in a vector system, you have all the information to create and change an image at any resolution. This means that you can transfer images across devices and printers without risk of loosing information.

That brings us to the Virtual Device Metafile format or VDM. Metafiles are essentially a serialization method for storing VDI commands to disk. Interestingly, the Metafile format does appear to have survived to the present day as the Computer Graphics Metafile format, although it doesn't appear to be binary compatible with the older VDM format. That being said, we now can understand what the blurb on the front of the box is all about - The Graphical File System is a way to store and load metafiles. Seems straightforward enough, and neat enough to check out. Let's get installing.

From A to Lattice C and All The Pain In-Between

Given the time period, for installation, I went with an emulated PC AT, PC-DOS 3.3, and an EGA card. EGA support seems to be a last minute addition, since the box doesn't menton it. That's not entirely surprising because the EGA card was publicly released late 1984, so it would have just been coming on the market as the Graphical File System was released. Both the manual and driver disks do directly reference EGA support however.

Copying Disks Over

In addition, since I expected to do some programming, I felt a good text editor was in order. PC-DOS 3.3 only ships with EDLIN, and I wanted something just a tad less bare bones. So, for this project, I installed Borland Brief, and got to it. Brief is a pretty decent editor, and while I never used it back in the day, it seemed pretty easy to pick up and run with. After getting it installed it was just a bit more effort to get CONFIG.SYS sorted.

CONFIG.SYS Edited for VDI Drivers

With the bare essentials taken care of, it was time to dig in a bit deeper. According to the manual, the GRID binary displays a reference image. Sure enough, it rendered on the first try. I didn't notice it until comparing it to the other graphics modes, but this isn't actually rendering correctly. Specifically, the image is not sitting in the correct location on screen, and its cut off. The CGA drivers in contrast appear to render the test graphic better, albeit with lower color fidelity.

GRID rendered in 16 color EGA 640x350 Mode

GRID rendered in 4 color CGA 320x200 Mode

I did try the other graphics modes, and as I mentioned in the video, the EGA monochrome one simply crashed. Meanwhile, the PCjr just went and said No. To be honest, the fact that there is even a jr driver seems weird because the basic VDI driver set occupies about 300 kilobytes of conventional memory. While it is possible to expand a jr that far, the cost combined with the jr's iffy reputation for software compatibility made me wonder who would even try it?

PCjr Booting Up. Note The 16-color Graphics

PCjr GRID Failure

Well, besides me. But I'm doing it in the interest of historical preservation. That's my justification and I'm sticking with it.

I didn't actually notice the resolution cutoff at the time, and it was only when going back to demonstrate CGA capabilities did I even realize that the image was cutoff. Once again, I don't know if this is a problem with PCem, or a problem with VDI since I don't have the physical card to test it. It is possible that since this was almost certainly developed on a pre-production EGA card (since the GFS product was released a few months before EGA cards hit the market), its doing something wrong. It won't be the first known example of IBM-branded software having incompatibles with still-to-be-released equipment (see this article on Xenix 286)

The other utility on the disks was METAFILE, which the manual calls the Interactive Interpreter. At first glance, it looks like some sort of drawing application, but looks here are deceptive.

The Interactive Interpreter Splash Screen

The Interactive Interpreter Main Interface

All this application is a way to display multiple metafiles and lay them out. Files can be rendered on screen, or sent to a printer or plotter. To be honest, I'm really not certain how this is useful. While you could (theoretically) lay out multiple metafiles for printing, and there's no doubt that someone indeed used the Interactive Interpreter to do so, without any way to tweak or edit images, it seems very limited in utility. You can't even save or load layouts. If it was meant as an example application, then they could at least included the source code to it.

Laying out metafiles to be rendered

Rendered metafiles

At this point, I thought most of the meat and potatoes of this package were based in the programming library, but just trying to get a working environment led to an entirely different set of issues.

The Graphical File System ships with development libraries for four compilers, Lattice C 2.0, IBM Fortran Compiler, IBM's Professional Fortran Compiler, and IBM's BASIC compiler. I legitimately don't know what the difference is between the two Fortran compilers, but in this case, it's a bit academic. The largest problem is that these really are the only compilers supported for one simple reason: the libraries are not in the OMF format!

To be honest, this was a little surprising. For the most part, development libraries and tools for x86 have been standardized around Intel's Object Module Format. OMF is ancient, it was already on version 4.0 in 1981. Instead, the libraries appear to be in some sort of proprietary format specific to each compiler. I had somewhat hoped that I might be able to use OpenWatcom in addition to period specific tools, but obviously, this wasn't meant to be.

To complicate issues, I had numerous issues with Lattice C. From what I have found, Lattice C wasn't exactly a well-regarded product, so it's perhaps unsurprising that I had some issues. To start off, the surviving documentation appears at best incomplete. While the scanned manuals do talk about the compiler components, and overall operation, there's no installation instructions or similar to be found here.

This failed Lattice C installation dumped files everywhere

Installation is handled through a series of batch files that have no error checking. Even after getting Lattice C installed 'properly' I still had numerous issues. First off, the IBM PC Linker was missing-in-action. This is at least understandable, when Lattice C 2.1 shipped in 1982, LINK.EXE was still included standard on the DOS disks. There's no reason for the compiler to not expect that the system provided linker is MIA. To make life even easier, the Graphical File System actually shipped with an updated LINK.EXE so I didn't even have to go digging through old archives to find a copy. Yay for usability!

Unfortunately, that's where the good ends. The compiler gives very terse error messages. For example, when trying to compile HELLO.C, I found that Lattice C often gave a "File Not Found" error, but didn't clearly indicate that it couldn't find stdio.h. This lead me down a rathole that made me believe for awhile that Lattice C's subdirectory support was buggy. It took me nearly a full day of fiddling to actually understand how quirky this compiler is. Even by early 80s standards, this is pretty horrid.

Hello World build failing because Lattice C couldn't find stdio.h

Even after resolving this, I still had larger problems: I couldn't get CMETA to link with the showmetc example code due to numerous issues. The first is that the Graphical File System was coded for Lattice C 2.0, and I was using 2.1 (which was the closest archived version). Even after resolving the initial hurdles, I had multiple link failures trying to get everything to build.

Failure to link SHOWMETC

It actually got to the point that I thought I was going to need to write-off Lattice C entirely, and it was around here I ended up installing IBM Fortran, which is amusing on the basis that it has a specific installation flag asking if you were on DOS 2.0+ or higher!

SETUP.BAT for IBM FORTRAN 2.0

I did manage to get the Fortran example to build with relatively little fanfare, but I really didn't want to code in FORTRAN if I could avoid it. Ultimately, I did work out the very long set of linker objects to build with Lattice C 2.1, but I was not entirely sure everything was working right.

Lattice C 2.1 Commands for SHOWMETC.C

For one, the reference image just doesn't seem to be rendering correctly. This could be due to differences in how GRID and SHOWMET{C|F} are coded. I also had issues related to timing loops; specifically, the demo code in both C and FORTRAN wants to pause before advancing to the next time; for the C code, the pause is handed through a for loop counting to 100,000. It's possible that improvements to the codegen in both Lattice C 2.1 made this run faster, but it doesn't explain why the FORTRAN code also appears to run too fast. As a reminder, I am running this on an (emulated) IBM PC AT which is a period correct machine for this software so I'm still surprised at this.

SHOWMETC - Note that the image renders differently than under GRID

It's shortly after getting the demonstration code compiling that I began to realize that something seemed missing ...

If we look at the manual's reference, there are 15 functions in total for the Graphical File System, all of which handle opening and rendering of metafiles. Aside from the special 'Virtual Device Metafile' VDI driver, there isn't even a way to create a Metafile out of the box: I had to use Harvard Graphics to make the examples we've seen up to this point.

List of Functions

A Convoluted Jigsaw Puzzle

To put it fairly bluntly, figuring out anything beyond this point was an exercise of frustration. I knew I was already dealing with some fairly obscure topics, but the utter lack of information was pretty astounding. A lot of what I initially found was based on research of the Graphical Kernel System, and the Professional Graphics Series described in the manual. I touched on these earlier, but it now time to go far more in-depth. To that end, I need to introduce one other piece of IBM history: the Professional Graphics Controller.

If you've never heard of the Professional Graphics Series, or the Professional Graphics Controller, well, I can't blame you.

The Professional Graphics Controller

Both are pretty obscure pieces of IBM history, and they weren't meant for end consumers. IBM actually had fairly large plans to turn the PC into a relatively low cost CAD workstation. The Professional Graphics Series, and the PGC card were the means to that end, and for a time, they represented the absolute best you could get out of an IBM PC machine. To understand the full impact and importance of the PGC, let's take a look at what IBM was offering at the time. Assuming we go with the most commonly available graphics card supported by IBM, we had essentially five standards: MDA, CGA, the PGC, and the soon-to-be-released EGA. Let's take them one at a time:

Starting from least capable to most capable, let me introduce IBM's official Monochrome Display Adapter, or MDA card.

IBM Monochrome Display and Print Adapter

MDA Font Example

Capable of doing 80 columns text modes, and pretty much nothing else, the MDA graphics card was pretty popular simply on the basis that it was ideal for text based work. It was also one of the two graphics choices that IBM had released with the IBM PC 5150 (along with CGA), and thus was by definition compatible with virtually everything. That being said, it was entirely a one trick pony. The MDA didn't offer any sort of graphics modes or even anything beyond 2-bit black and white coloring. Despite its limitations, the MDA tended to be pretty popular, and I generally remember more computers with an MDA adapter than CGA. This is due to the fact that the CGA card tended to be fairly lackluster in text modes, and often ran in 40 columns mode due to limitations of many color monitors of the era.

In short, with the MDA you could make text look nice.

The other officially IBM sanctioned graphcis cards was the CGA card. More specifically, let's dig into the 'Color Graphics' part of it.

Even in vintage tech circles, people don't tend to fondly remember CGA cards. Technically speaking, it's capabilities weren't bad for the period in which it was introduced. With its multiple graphics and text modes, the CGA card was at least capable of doing some interesting things. However, the physical CGA card was hamstrung by low memory, and very low bandwidth. Even putting that aside, it was difficult to reach the CGA's full graphics potential on many PCs of the era.

To reach it's full potential, an CGA card needed an RGBI monitor, and a fairly loaded PC at the time. That would have cost a pretty penny, and even when fully decked out, the CGA's best isn't anything to really write home about. To put this in context: many 8-bit micros of the era could general match or outclass it. Even for the period, the only thing that was semi-unique to it was the bitmap 640x200 2-color mode.

Assuming you actually wanted the "color" part of color graphics, the CGA card was not generally capable of high resolution images. At an absolute best, assuming that you were using a RGB monitor, the CGA card could only display four colors at a times out of a palette of sixteen with a max resolution of 320x200. To add final insult to injury, the color palette couldn't be freely set, you were limited to relatively small set of options, ontop of which that many applications were further limited to the semi-default 'cyan-purple-white'.

Commander Keen Title in CGA

While it is technically possible to get more out of a CGA card, in general, you start running into numerous hardware limitations that make it difficult to impossible. Probably the best examples of what a CGA card could do when pushed to the limit is the 8088 Corruption, and 8088 Domination which showcase full motion video playing in 16-color mode on a CGA card!

If we're sorting by capabilities, the EGA card comes second from the last of graphics adapters from this time period. Released in 1984, the EGA card was essentially a strict upgrade over the CGA, and was in general, backwards compatible. EGA would essentially be the de-facto standard until the 90s. While a specific EGA card might be more limited, under EGA, a compatible adapter could display a 16-color image of a resolution of 640×350. As one can see from this screenshot, running an application like AutoCAD becomes much more reasonable under these constraints.

AutoCAD 2.15 in EGA

The largest problem with the EGA card for CAD work is that the card was not accelerated. That meant the main system CPU would have to re-render an image and then send it to the EGA card to display it. Even with simple applications, its generally possible to see a 'render lag' as the main CPU grinds away at rendering an image under these circumstances. The Professional Graphics Controller would utterly leave the EGA card in the dust however.

PGC Output on a IBM 5175

To put it bluntly, beside being a three PCB sandwich, the Professional Graphics Controller is a beast of a graphics adapter. Capable of displaying 256 colors at 640x480, the Controller also had it's own dedicated 8086 processor and capable of running accelerated drawing commands. This is essentially the same as modern day 2D and 3D acceleration, and the end results seem fairly impressive. For compatibility reasons, the PGC also could emulate a CGA card, although from what I can tell, this emulation was fairly incomplete. To be honest though, it's hard to find anything that can take advantage of the PGC beside CAD software, and there's very limited support for it in emulation.

I wanted to do a demo of the PGC, as MAME in theory can emulate the controller, but in practice, I couldn't get MANE to run; instead it would die repetitively with POST code 101 no matter how I tried to start it. Although I couldn't get MAME's PGC emulation to work, it did lead me to an interesting example applications, and understanding of just what was missing in the Graphical File System.

IAE/ORAU Long Term Global Energy Economic Model

If someone told me that I would find the answer to the Graphical File System's mysteries in a CO2 modelling application written for the IEC in the mid-80s, I would have been really skeptical.

This application was linked off the MAME Professional Graphics Series page, and it includes binaries, VDI drivers, and source code (in FORTRAN) for building against the IBM PC Graphical Kernel System.

Graphical Kernel System Boxart

Yes, you read that right, the IBM PC Graphical Kernel System. IBM, in their own infinite wisdom, created a product with the same name as the standard. As you can imagine, this made searching for information a real joy. At the time I started production on this video, the Graphical Kernel System hadn't been preserved, and there was going to be a fairly long conversation about how these niche items never seem to get preserved. However, in this case, fate intervened.

I'm a member of several computer tech groups, and most notably, the Computer Reset Warehouse group, a place that has been featured on quite a few retro-tech videos. By sheer chance, all three volumes of the Grpahical Kernel System cropped up at the warehouse, and the finder had posted an image to the group. My eye caught on the distinctive grey and green striping, and a few others had noticed it as well since I had brought up the Graphical File System in another group. I sent a DM to the finder, and he not only dumped the disks, they also scanned the manuals!

In short, another piece of software was saved from the dustbin of history!

In Closing

This dig into IBM's early history has been pretty interesting but very time consuming. I may do a follow-up on the Graphical Kernel System at a later point, but I think it's time to put this topic to bed for now. At least for the moment, what I ahve is an add-on library to another library, which was intended for use with an obscure piece of IBM hardware. I don't think you get odder content than that!

I do hope you all enjoyed this look at IBM strangeness, and I hope you'll all give a look, like, and follow on YouTube. It does make a real difference! Next time, we'll likely get back to working on the Intel branded EISA workstation, and then I have a few other things in the works for the start of the New Year.

~ 73 de NCommander

NOTE: Many of the graphics adapter pictures are from MinusZeroDegrees.net which has a large collection of information on old IBM add-on cards.